If you find yourself on a winter morning shooting the sunrise shadows of the frozen dunes of the Great Sand Dunes National Park, by mid-morning you’ll be needing a hot breakfast to warm your bones.1

The Great Sand Dunes is an ongoing project that I’ve written about several times here:

A Desert of Light & Shadows

The images I’m sharing here and in my next two posts intrigue me more than most I’ve taken in quite awhile.

That was the situation in which my daughter and I found ourselves last February. With the shadows gone and several hours before they’d return with the late-afternoon sun, we lit out for Crestone, a nearby town with a population of 120 on a good day.

With only one bar on my phone and no local map to consult, I had to pull over a couple of times to get directions to Crestone. The roads aren’t marked for tourists. And each time the directions came with the free advice for me to visit “The Ziggurat,” which they promised that anyone in town could point me to.

“It’s a tower that gets you closer to God,” a storekeeper along the highway leading to Crestone explained to me.

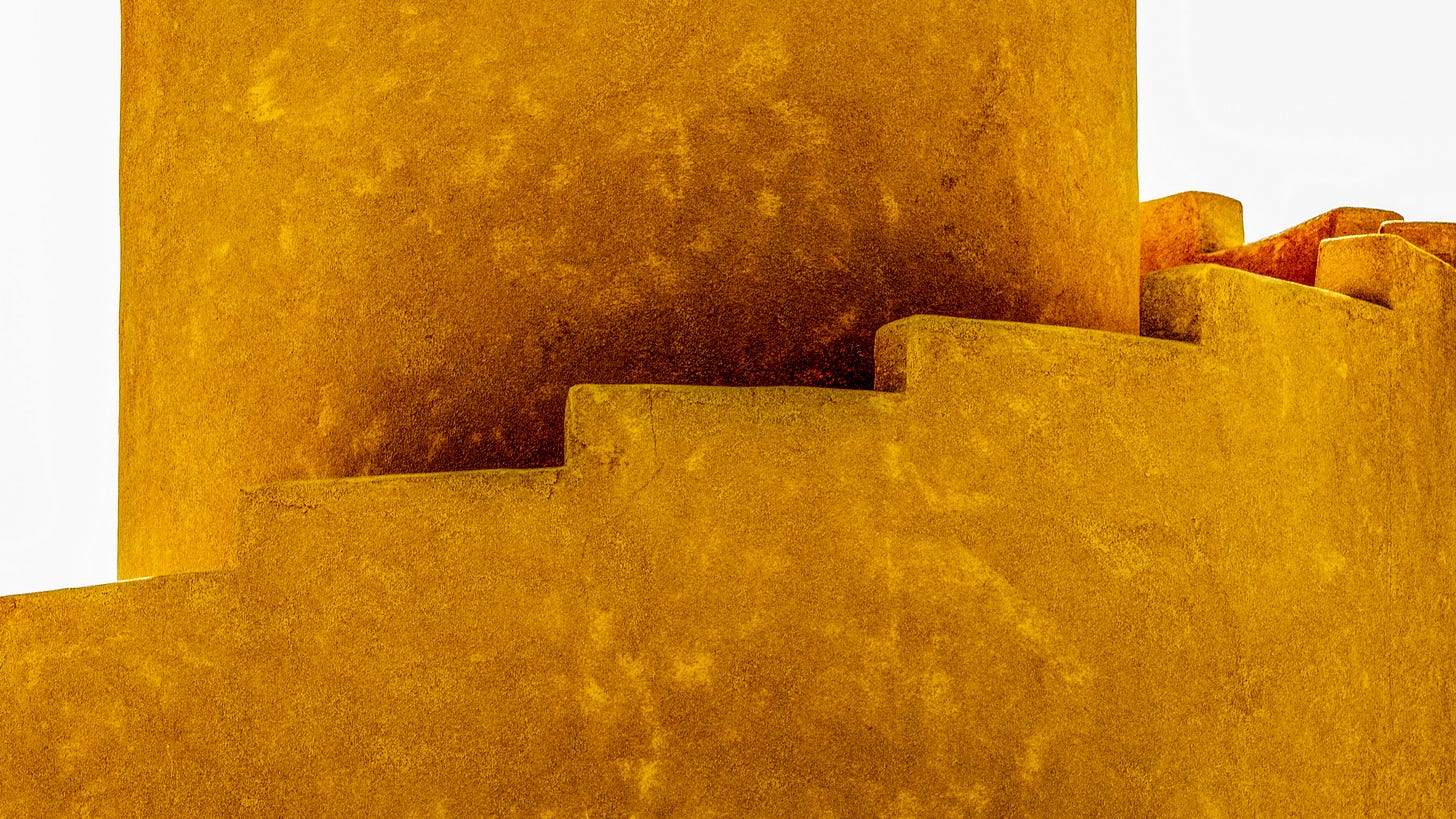

A ziggurat is a structure made of sun-dried bricks, dating back to ancient Mesopotamia. They were built as dwelling places for the gods, usually as shrines atop large complexes of buildings.

The Crestone Ziggurat shares what is known of the original design features of the ancient structures, but at less than 50 years old, it’s anything but ancient.

The story of how it came to be built in Crestone is worth a Substack minute.

In its early 20th Century heyday, Crestone was a robust mining town of nearly 2,000. But as the mines shut down over the years, the population dwindled to barely nothing.

In the early 1970’s, AZLCC, a development company, turned the land grant surrounding Crestone into a large residential subdivision that brought in a few new seasonal residents, including Hanne Marstrand Strong and her husband Maurice Strong, a Canadian money man who owned a controlling interest in AZLCC.

By Mrs. Strong’s account, one day a local man, a teacher of some sort, knocked on her door — a visit that would change Crestone for good.

“He was an old chap who had a lot of students in the valley,” Mrs. Strong told the New York Times in 2011. “He came right up and announced, ‘I predicted in the ’60s that a foreigner would come here and build an international religious center here. What took you so long?’”

So that’s precisely what Hanne Marstrand Strong did. She started a foundation —the Manitou Foundation — that would ultimately give nine land grants to religious organizations, including a Carmelite Catholic monastery, several Buddhist communities, and Shinji Shumeikai, a Japanese New Religion.

As the spiritual centers attracted new practitioners, additional religious groups and sects moved in. Today Crestone – which sits at the base of the western slope of the Sangre de Cristo Range — Blood of Christ — hosts one of the largest and most diverse groupings of spiritual communities in the world.2

And what of the Ziggurat?

In 1978, Najeeb Halaby — the father of Queen Noor of Jordan and a former CEO of Pan Am Airways — purchased a plot of land for $10 and commissioned the Ziggurat to be built on it as a place for prayer and meditation.

And here we are.

A tower that gets one closer to God.

All photos were taken in February, 2024.

Crestone also had a Netflix moment, thanks to a documentary on “Mother God,” the name taken by Amy Carlson, who claimed to be a 19-million-year old entity and a reincarnate of Jesus Christ. She and her followers sold New Age stuff on the Internet and advocated the drinking of a colloidal silver to stave off Covid. Carlson would lose all motor functions in her final days in Crestone where she died, having been drawn to the area for its spiritual energy. After her death, her followers kept her body in her house for several weeks, awaiting galactic beings to take it away. The FBI arrived first to claim it.

Wow, the images and the story blew me away!! Thank you for sharing it all.

Love this series.